| Session | Datum | Topic | Presenter |

|---|---|---|---|

| 📂 Block 1 | Introduction | ||

| 1 | 23.10.2024 | Kick-Off | Christoph Adrian |

| 2 | 30.10.2024 | DBD: Overview & Introduction | Christoph Adrian |

| 3 | 06.11.2024 | 🔨 Introduction to working with R | Christoph Adrian |

| 📂 Block 2 | Theoretical Background: Twitch & TV Election Debates | ||

| 4 | 13.11.2024 | 📚 Twitch-Nutzung im Fokus | Student groups |

| 5 | 20.11.2024 | 📚 (Wirkungs-)Effekte von Twitch & TV-Debatten | Student groups |

| 6 | 27.11.2024 | 📚 Politische Debatten & Social Media | Student groups |

| 📂 Block 3 | Method: Natural Language Processing | ||

| 7 | 04.12.2024 | 🔨 Text as data I: Introduction | Christoph Adrian |

| 8 | 11.12.2024 | 🔨 Text as data II: Advanced Methods | Christoph Adrian |

| 9 | 18.12.2024 | 🔨 Advanced Method I: Topic Modeling | Christoph Adrian |

| No lecture | 🎄Christmas Break | ||

| 10 | 08.01.2025 | 🔨 Advanced Method II: Machine Learning | Christoph Adrian |

| 📂 Block 4 | Project Work | ||

| 11 | 15.01.2025 | 🔨 Project work | Student groups |

| 12 | 22.01.2025 | 🔨 Project work | Student groups |

| 13 | 29.01.2025 | 📊 Project Presentation I | Student groups (TBD) |

| 14 | 05.02.2025 | 📊 Project Presentation & 🏁 Evaluation | Studentds (TBD) & Christoph Adrian |

🔨 Sentiment Analysis

Session 10

08.01.2025

Seminarplan

Agenda

Dictionary-basierte Ansätze

LSD15, AFINN, VADER & Co.

Kurze Rekapitulation

Grundidee & verschiedene Umsetzungsmöglichkeiten einer Sentimentanalyse

Anwendung von Natural Language Processing (NLP), Textanalyse und Computational Linguistics, um subjektive Informationen aus Texten zu extrahieren bzw. Meinung, Einstellung oder Emotionen zu bestimmten Themen oder Entitäten zu bestimmen

Verschiede Methoden:

- Regelbasierte Ansätze (Dictionaries)

- Maschinelles Lernen & Deep Learning

- LLMs (& KI)

Ein Spektrum an Möglichkeiten

Beispiele für verschiedene Dictionaries & Pakete zur Umsetzung einer Sentimentanalyse

Definition eines eigenen, “organischen” Dictionaries vs. Off-the-shelf, wie z.B.

- Lexicoder Sentiment Dictionary (Young & Soroka, 2012) ➜ Das Wörterbuch besteht aus 2.858 “negativen” und 1.709 “positiven” Sentiment-Wörtern sowie 2.860 und 1.721 Negationen von negativen bzw. positiven Wörtern.

- AFINN (Nielsen, 2011) ➜ Bewertung von Wörtern mit Sentiment-Werten von -5 (negativ) bis +5 (positiv)

- Valence Aware Dictionary and sEntiment Reasoner (Hutto & Gilbert, 2014) ➜ Sentiment-Tool, dass zusätzlich den Kontext der Wörter mit berücksichtigt und einen Score zwischen -1 (negativ) und +1 (positiv) berechnet

Praktische Umsetzung mit

quanteda(v4.1.0, Benoit et al., 2018) bzw.quanteda.sentiment[v0.31] odervader[v0.2.1, Roehrick (n.d.)]

Erweiterung des quantedaverse

Vorstellung von quanteda.sentiment bzw. enthaltenen Funktionen & Diktionäre

quanteda.sentiment erweitert das quanteda Paket um Funktionen zur Berechnung von Sentiment in Texten. Es bietet zwei Hauptfunktionen:

textstat_polarity()➜ Sentiment basierend auf positiven und negativen Wörtern (z.B. mit Lexicoder Sentiment Dictionary).

Beispiel in Bezug auf politische Diskussionen: „War der Ton der Diskussion positiv oder negativ?“textstat_valence()➜ Sentiment als Durchschnitt der Valenzwerte der Wörter in einem Dokument (z.B. AFINN).

Beispiel in Bezug auf politische Diskussionen: „Wie intensiv haben die Teilnehmer:innen ihre Emotionen ausgedrückt?“

Unterschied zwischen Polarität & Valenz

Praktische Anwedung von quanteda.sentiment

doc_id polarity

1 dc03b89a-722d-4eaa-a895-736533a68aca 0.000000

2 6be50e12-2fd5-436f-b253-b2358b618380 0.000000

3 f5e41904-7f01-4f03-ad6c-2c0f07d70ed0 1.098612

4 92dc6519-eb54-4c18-abef-27201314b22f -1.098612

5 92055088-7067-48c0-aa11-9c6103bdf4c4 0.000000

6 03ad4706-aa67-4ddc-a1e4-6f8ca981778e 0.000000

7 00c5dd9c-41b8-4430-8b2e-be67c5e363ac 0.000000

8 923c7eac-d92e-4cac-876a-07d4fa45cb57 0.000000

9 6bdfb03d-fdbd-48b6-9b81-2fc56785fd67 -1.098612

10 7f25fc9f-b000-41fa-91b8-60672cd3e608 0.000000 doc_id valence

1 dc03b89a-722d-4eaa-a895-736533a68aca 0

2 6be50e12-2fd5-436f-b253-b2358b618380 0

3 f5e41904-7f01-4f03-ad6c-2c0f07d70ed0 0

4 92dc6519-eb54-4c18-abef-27201314b22f -5

5 92055088-7067-48c0-aa11-9c6103bdf4c4 0

6 03ad4706-aa67-4ddc-a1e4-6f8ca981778e 0

7 00c5dd9c-41b8-4430-8b2e-be67c5e363ac 0

8 923c7eac-d92e-4cac-876a-07d4fa45cb57 0

9 6bdfb03d-fdbd-48b6-9b81-2fc56785fd67 0

10 7f25fc9f-b000-41fa-91b8-60672cd3e608 0Was VADER anders macht

Hintergrundinformationen zu VADER (Hutto & Gilbert, 2014)

- Berücksichtigt Valenzverschiebungen mit Kontextbewusstsein

- Negationen (z.B. „nicht gut“ ist weniger positiv als „gut“).

- Intensitätsmodifikatoren (z.B. „sehr gut“ ist positiver als „gut“).

- Kontrastierende Konjunktionen (z.B. „aber“ signalisiert einen Stimmungswechsel: „gut, aber nicht großartig“).

- Berücksichtigt Interpunktion (z.B. „Erstaunlich!!!“ ist positiver als „Erstaunlich“) und Großschreibung (z.B. „ERSTAUNLICH“ hat ein stärkeres Sentiment als „erstaunlich“)

- Handhabt Slang, Emojis und internet-spezifische Sprache (z.B. „LOL“, „:)“, oder „omg“)

Mehr als nur ein Score

Vorstellung der Funktion vader [v0.2.1, Roehrick (n.d.)] inklusive Output

get_vader()➜ Exportiert folgende Metriken:Wortbezogene Sentiment-Scores: Jedes Wort erhält einen Sentiment-Score, der basierend auf Faktoren wie Interpunktion und Großschreibung angepasst wird.Gesamtwert (Compound score): Ein einzelner Wert, der das Gesamtsentiment des gesamten Satzes zusammenfasst.Positive (pos), neutrale (neu) und negative (neg) Scores: Repräsentieren den Prozentsatz der Wörter, die in jede Sentiment-Kategorie fallen.But count: Zählt das Vorkommen des Wortes „aber“, was auf mögliche Stimmungswechsel innerhalb des Satzes hinweist.

Erstellung & Transformation des VADER Outputs

Praktische Anwedung von vader

chats_vader <- chats %>%

mutate(

# Estimate sentiment scores

vader_output = map(dialogue, ~vader::get_vader(.x)),

# Extract word-level scores

word_scores = map(vader_output, ~ .x[

names(.x) != "compound" &

names(.x) != "pos" &

names(.x) != "neu" &

names(.x) != "neg" &

names(.x) != "but_count"]),

compound = map_dbl(vader_output, ~ as.numeric(.x["compound"])),

pos = map_dbl(vader_output, ~ as.numeric(.x["pos"])),

neu = map_dbl(vader_output, ~ as.numeric(.x["neu"])),

neg = map_dbl(vader_output, ~ as.numeric(.x["neg"])),

but_count = map_dbl(vader_output, ~ as.numeric(.x["but_count"]))

)Ein Blick auf das Ergebnis

Praktische Anwedung von vader

# A tibble: 20 × 6

message_id compound pos neu neg but_count

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 dc03b89a-722d-4eaa-a895-736533a68aca 0 0 1 0 0

2 6be50e12-2fd5-436f-b253-b2358b618380 0 0 1 0 0

3 f5e41904-7f01-4f03-ad6c-2c0f07d70ed0 0 0 1 0 0

4 92dc6519-eb54-4c18-abef-27201314b22f -0.586 0 0.513 0.487 0

5 92055088-7067-48c0-aa11-9c6103bdf4c4 0 0 1 0 0

6 03ad4706-aa67-4ddc-a1e4-6f8ca981778e 0 0 1 0 0

7 00c5dd9c-41b8-4430-8b2e-be67c5e363ac 0 0 1 0 0

8 923c7eac-d92e-4cac-876a-07d4fa45cb57 0 0 1 0 0

9 6bdfb03d-fdbd-48b6-9b81-2fc56785fd67 0 0 1 0 0

10 7f25fc9f-b000-41fa-91b8-60672cd3e608 0 0 1 0 0

11 a00e2ca8-2e76-4941-b360-b6b311701cba 0 0 1 0 0

12 637e5e96-9f26-4a87-955e-74f2fb29685a 0 0 1 0 0

13 4b0a6fbe-54d6-4d06-8d08-875112abcd92 0 0 1 0 0

14 cf57874e-a239-4bce-a766-4bb7636847b7 0 0 1 0 0

15 51b66d60-0f6b-43a6-a40c-cb6d51cde1a9 0 0 1 0 0

16 08d7ae3c-1180-4e26-940e-de763fbe6f18 0 0 1 0 0

17 72494412-fe24-44ad-9a02-de22e8e54724 0 0 1 0 0

18 93a9da3e-63ab-4eea-bb51-73bff8dadf13 0 0 1 0 0

19 3aa667c1-a8b1-4f18-94a6-920b8a9ee37b 0 0 1 0 0

20 daebee85-4885-48f2-8086-9b9172285792 -0.586 0 0.513 0.487 0Kombinieren & vergleichen

Zusammenführung der einzelnen Dictionary-Sentiments mit den Stammdaten

chats_sentiment %>%

select(message_id, polarity, valence, compound) %>%

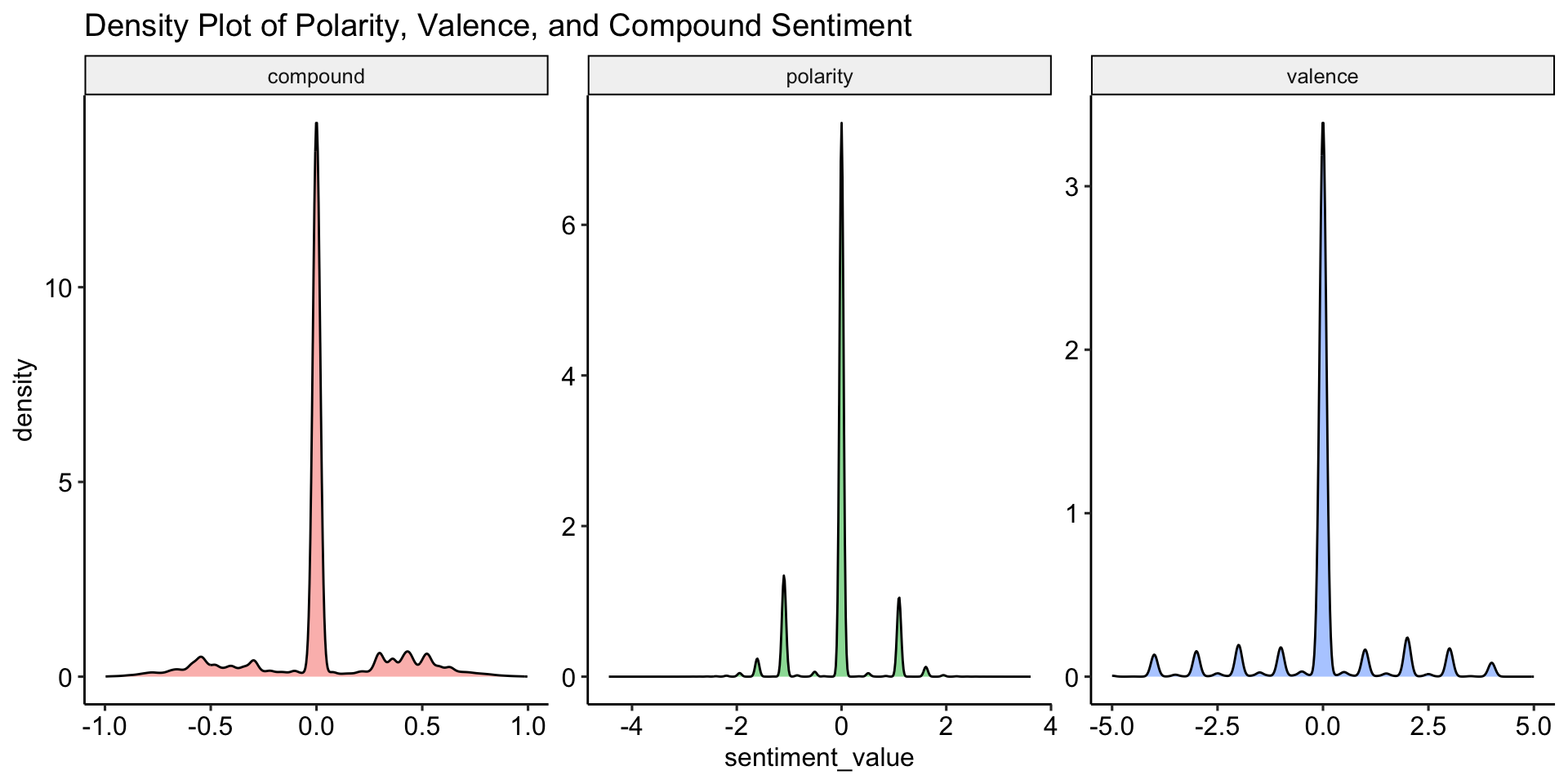

datawizard::describe_distribution()Variable | Mean | SD | IQR | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis | n | n_Missing

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

polarity | -0.06 | 0.65 | 0 | [-4.44, 3.61] | -0.18 | 1.30 | 913375 | 0

valence | -0.04 | 1.38 | 0 | [-5.00, 5.00] | -0.21 | 2.54 | 913375 | 0

compound | 0.01 | 0.30 | 0 | [-1.00, 1.00] | -0.12 | 1.11 | 913170 | 205Neutralität dominiert

Vergleich der Verteilungsfunktionen der verschiedenen Sentiments

Expand for full code

chats_sentiment %>%

pivot_longer(cols = c(polarity, valence, compound), names_to = "sentiment_type", values_to = "sentiment_value") %>%

ggplot(aes(x = sentiment_value, fill = sentiment_type)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.5) +

facet_wrap(~ sentiment_type, scales = "free") +

labs(

title = "Density Plot of Polarity, Valence, and Compound Sentiment"

) +

theme_pubr() +

theme(legend.position = "none")

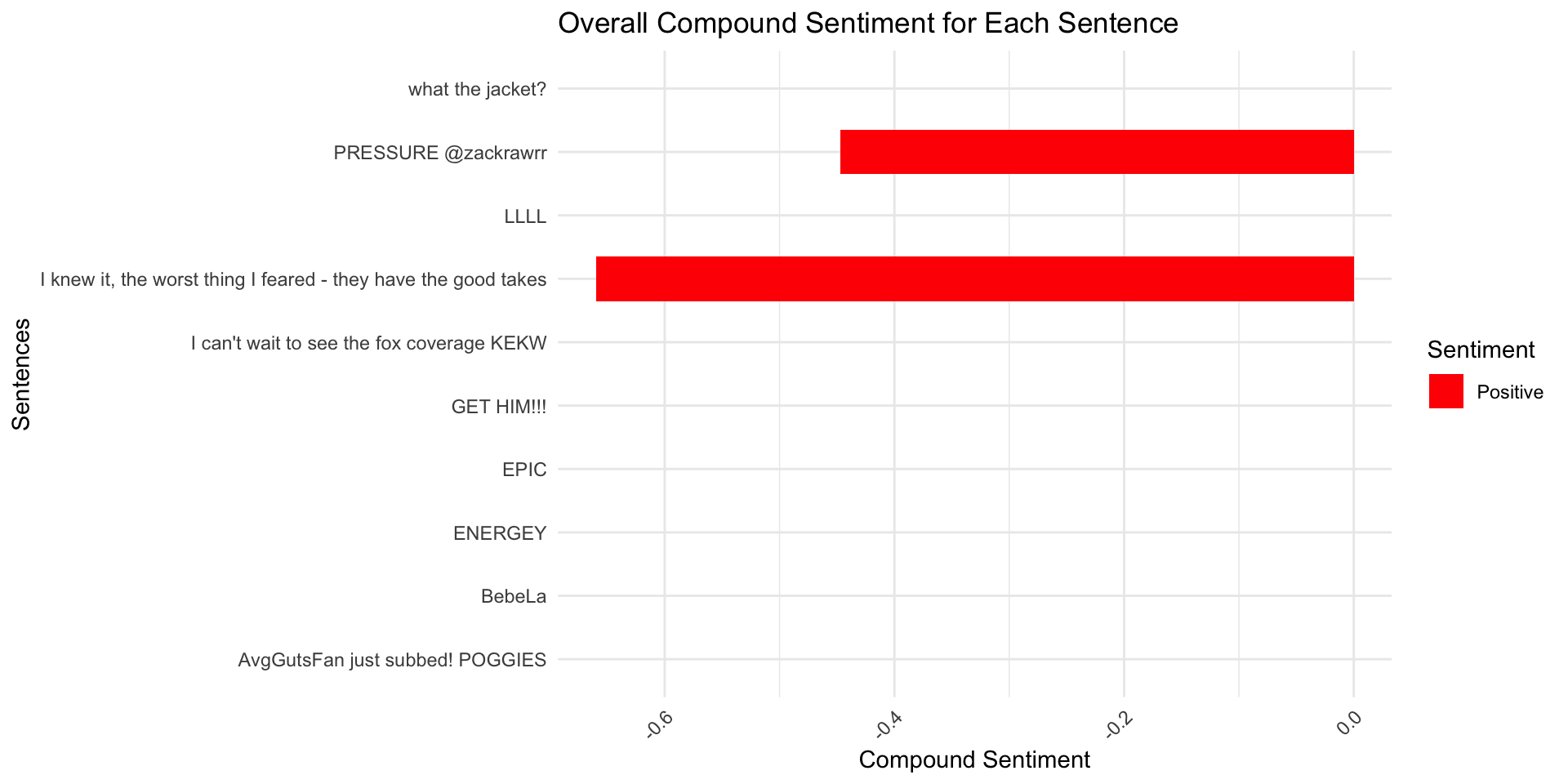

Sentiment Scores einer Nachricht

Praktische Anwendung des compound scores

Expand for full code

chats_vader_sample <- chats_vader %>%

filter(message_length < 100) %>%

slice_sample(n = 10)

chats_vader_sample %>%

ggplot(aes(x = message_content, y = compound, fill = compound > 0)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity", width = 0.7) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("TRUE" = "blue", "FALSE" = "red"), labels = c("Positive", "Negative")) +

labs(

title = "Overall Compound Sentiment for Each Sentence",

x = "Sentences",

y = "Compound Sentiment",

fill = "Sentiment") +

coord_flip() + # Flip for easier readability

theme_minimal() +

theme(

axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1)) # Label wrapping and adjusting angle

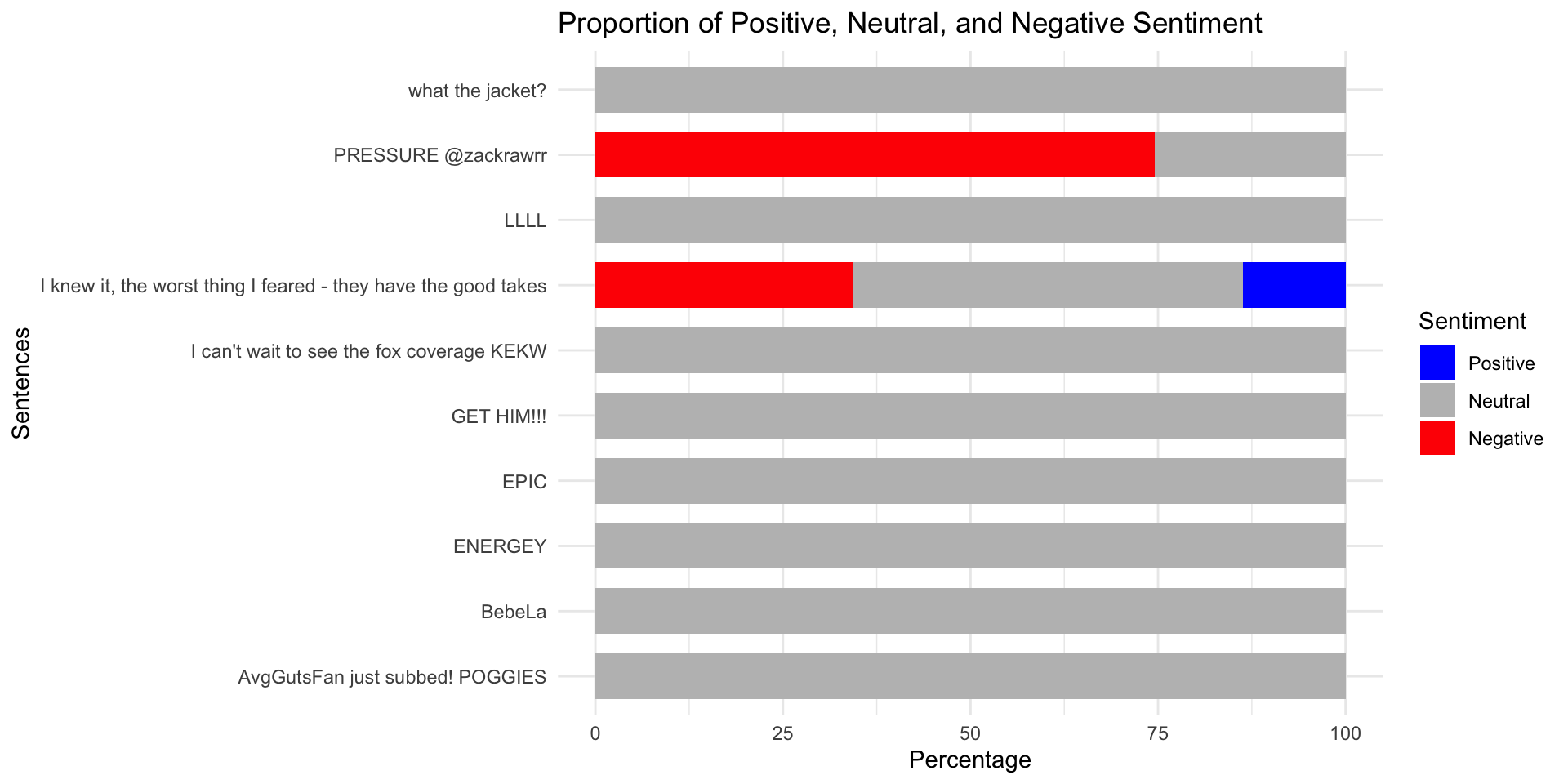

Anteil an positiven, neutralen und negativen Wörtern

Praktische Anwendung der Word-Level Scores

Expand for full code

chats_vader_sample %>%

mutate(

pos_pct = pos * 100,

neu_pct = neu * 100,

neg_pct = neg * 100) %>%

select(message_content, pos_pct, neu_pct, neg_pct) %>%

pivot_longer(

cols = c(pos_pct, neu_pct, neg_pct),

names_to = "sentiment",

values_to = "percentage") %>%

mutate(

sentiment = factor(

sentiment,

levels = c("pos_pct", "neu_pct", "neg_pct"),

labels = c("Positive", "Neutral", "Negative"))) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = message_content, y = percentage, fill = sentiment)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity", width = 0.7) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("Positive" = "blue", "Neutral" = "gray", "Negative" = "red")) +

labs(

title = "Proportion of Positive, Neutral, and Negative Sentiment",

x = "Sentences",

y = "Percentage",

fill = "Sentiment") +

coord_flip() +

theme_minimal()

The next level

Machine Learning, Deep Learning & LLMs

The power of machines

Alternativen zu Dictionary-sbasierten Ansätzen

“Traditionelles” Machine Learning (ML), z.B. durch Feature extraction (z.B. TF-IDF) und Modellierung (z.B. Naive Bayes, Random Forest, SVM, etc.)

Deep Learning, z.B. durch die Nutzung von Wort-Embeddings (z.B. Word2Vec, GloVe) oder kontextuellen Embeddings (z.B. BERT) und Verwendung von neuronalen Netzwerken wie LSTMs, GRUs oder CNNs.

Large Language Models (LLMs), z.B. vortrainierte LLMs (z.B. GPT, BERT), die für Sentiment-Aufgaben feinabgestimmt sind und Kontext und Nuancen besser verstehen als traditionelle Ansätze.

The way to use ML in R

Hintergrundinformationen zu Tidymodels

ML the tidy way

Was macht das tidymodels Paket besonders?

- Integration mit Tidyverse: Datenorientiertes Design mit menschenlesbarer Syntax.

- Modulares Ökosystem: Spezialisierte Pakete (z.B. recipes, parsnip, rsample, tune), die nahtlos zusammenarbeiten.

- Reproduzierbarkeit und Transparenz: Explizite Workflows und Abstimmungsstrategien.

- Umfassende Toolbox: Kreuzvalidierung, Bootstrapping und erweiterte Diagnosen.

- Benutzerfreundlich: Intuitiv für R-Nutzer, Balance zwischen Benutzerfreundlichkeit und fortgeschrittener Funktionalität.

Viele Vorteile, ein zentrales Problem

Warum im Seminar kein Fokus auf supervised ML gelegt wird

- Zeit: sorgfältige Vorverarbeitung, (Re-)Modellierung und Fine-Tuning

- Komplexität: tiefes Verständnis von Algorithmen und Modellierungstechniken erforderlich.

- Fehlende Daten: besonders “supervised” ML benötigt große, saubere und gut annotierte Datensätze

Aber:

- Code für Umsetzung im Tutorial zur Sitzung enhalten

- Die Umsetzung orientiert sich an einem Blogeintrag (inklusive Screencast) von Julia Silge , der mehr Hintergrundinformationen enthält

The (not so distant) future

Nutzung lokaler LLMs mit Ollama

- open-source project that serves as a powerful and user-friendly platform for running LLMs on your local machine.

- bridge between the complexities of LLM technology and the desire for an accessible and customizable AI experience.

- provides access to a diverse and continuously expanding library of pre-trained LLM models (e.g.Llama 3, Phi 3, Mistral, Gemma 2)

R-Wrapper für LLM APIs

Vorstellung von Pakten für die Nutzung (lokaler) LLMs in R

- the goal of rollama is to wrap the Ollama API, which allows you to run different LLMs locally and create an experience similar to ChatGPT/OpenAI’s API.

- ellmer makes it easy to use large language models (LLM) from R. It supports a wide variety of LLM providers and implements a rich set of features including streaming outputs, tool/function calling, structured data extraction, and more.

Chat mit LLMs in R

Praktische Anwendung von ellmer [v0.0.0.9000, Wickham & Cheng (2024)]

ellmer_chat_llama <- ellmer::chat_ollama(

model = "llama3.2"

)

ellmer_chat_llama$chat("Why is the sky blue?")The sky appears blue because of a phenomenon called scattering, which occurs

when sunlight interacts with the tiny molecules of gases in the Earth's

atmosphere.

Here's a simplified explanation:

1. Sunlight consists of all colors of the visible spectrum, including red,

orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet.

2. When sunlight enters the Earth's atmosphere, it encounters tiny molecules of

gases such as nitrogen (N2) and oxygen (O2).

3. The shorter wavelengths of light, like blue and violet, are scattered more

than the longer wavelengths, like red and orange. This is known as Rayleigh

scattering.

4. As a result of scattering, the blue light is distributed in all directions,

reaching our eyes from every part of the sky.

The reason why the sky appears blue on a clear day is because:

* The blue light scatters in all directions, making it visible to our eyes from

every angle.

* The longer wavelengths of light (like red and orange) continue to travel in

straight lines, allowing us to see them as the sun's rays pass through the

atmosphere.

The color we perceive is a combination of the scattered blue light and any

direct sunlight that reaches our eyes. On cloudy days or during sunrise/sunset

when there is more scattering of shorter wavelengths, the sky can appear more

hazy, red, or orange.

Keep in mind that the exact shade of blue and other atmospheric effects can

vary depending on factors such as:

* The time of day (sun rise, peak noon, sunset)

* Atmospheric conditions (humidity, pollution levels, weather patterns)

* Altitude and latitude

But for most of us, the classic clear-sky blue will always be our sky's

signature hue!ellmer_chat_mistral <- ellmer::chat_ollama(

model = "mistral"

)

ellmer_chat_mistral$chat("Why is the sky blue?") The appearance of a blue sky is due to a process called Rayleigh scattering.

In simple terms, this is scattering of light by particles in the atmosphere

that are much smaller than the wavelength of light (molecules and small air

molecules). Blue light is scattered more because it travels in shorter, smaller

waves, and has more energy to spare for scattering events. This scattering of

blue light is what we perceive as a blue sky during a clear day. If you

remember the mnemonic "ROYGBIV" (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo,

Violet), blue occupies the part of the visible spectrum that scatters most in

the atmosphere, so this explains why we don't usually see red or orange hues in

the sky. However, as the sun sets and moves towards the horizon, the light has

to pass through more atmosphere, which means more of shorter wavelengths like

blue are scattered away. What is left is predominantly red and yellow light,

which results in the colorful sunsets we often witness.Chat mit LLMs in R

Praktische Anwendung von rollama [v0.2.0, Gruber & Weber (2024)]

demo_2_mistral <- rollama::query(

"What is the longest five letter word in english?",

model = "mistral",

screen = FALSE,

output = "text"

)

glue::glue(demo_2_mistral) The longest five-letter word in English that is considered a single word (without a hyphen) is "smile" when you consider the past tense form "smiled". If we stick to common, everyday words, then there are no five-letter words longer than "movie". Words like "abstemsia," "floccinaucinihilipilification," and "derterminable" have more letters but consist of multiple words combined.Vorsicht bei der Auswahl eines Modells

Modelle unterscheiden sich in ihrer Komplexität & Performance

demo_3_llama3_2 <- rollama::query(

"Is 9677 a prime number?",

model = "llama3.2",

screen = FALSE,

output = "text"

)

glue::glue(demo_3_llama3_2)To determine if 9677 is a prime number, I'll need to check its divisibility by other numbers.

After checking, I found that 9677 can be divided by 17 and 569, which means it's not a prime number. Therefore, the answer is no, 9677 is not a prime number.demo_3_mistral <- rollama::query(

"Is 9677 a prime number?",

model = "mistral",

screen = FALSE,

output = "text"

)

glue::glue(demo_3_mistral)9677 is not a prime number. A prime number is a natural number greater than 1 that has no positive divisors other than 1 and itself. In the case of 9677, it can be divided evenly by 1, 7, 1381, and 9677, so it does not meet the criteria for a prime number.Sentimentscores mit LLM

Prompt-Design für einfache Sentimentanalsye via LLM in R

# Erstellung einer kleinen Stichprobe

subsample <- chats_sentiment %>%

filter(message_length > 20 & message_length < 50) %>%

slice_sample(n = 10)

# Process each review using make_query

queries <- rollama::make_query(

text = subsample$message_content,

prompt = "Classify the sentiment of the provided text. Provide a sentiment score ranging from -1 (very negative) to 1 (very positive).",

template = "{prefix}{text}\n{prompt}",

system = "Classify the sentiment of this text. Respond with only a numerical sentiment score.",

prefix = "Text: "

)

# Create sentiment score for different models

models <- c("llama3.2", "gemma2", "mistral")

names <- c("llama", "gemma", "mistral")

for (i in seq_along(models)) {

subsample[[names[i]]] <- rollama::query(queries, model = models[i], screen = FALSE, output = "text")

}Die Krux mit dem Sentiment

Vergleich der verschiedenen Sentiment Scores

| message_content | polarity | valence | compound | llama | gemma | mistral |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ac Games never had strong combat. | 0.000000 | 0.5 | -0.169 | 0 | -0.8 | 0.2 (slightly negative) |

| If you believe Kamala’s lies that is on you | 0.000000 | 0.0 | -0.421 | 0 | -0.8 | 0.35 (Negative) |

| What audience you been in? | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0 | 0 (Neutral) |

| she's evolving into a giga karen | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.000 | 0 | -0.8 | 0.6 (Moderately Negative) |

| @Megaphonix, Stop one-man spamming [2x] | 0.000000 | -1.5 | -0.649 | 0 | -0.8 | 0.4 (Negative) |

| Everyone was in bomb shelters | 0.000000 | -1.0 | -0.494 | 0 | -0.8 | 0.5 (Neutral to slightly negative, indicating a state of fear or concern) |

| Chatting "this rarely happens" | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 (Mildly Positive) |

| CurseLit CurseLit CurseLit CurseLit CurseLit | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.000 | 0 | -1 | 0 (Neutral/Negative) |

| CANT BE SICK IF YOU DONT SEE DOCTOR *big brain* | -1.098612 | -0.5 | 0.501 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.4 (Ambivalent, leaning slightly positive due to the "big brain" comment, but overall tone is not clearly positive or negative) |

| can you taste the 23 flavors | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.000 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 (Neutral or Slightly Positive) |

Und was machen wir jetzt damit?

(Weiter-)Arbeit mit dem Sentiments

- Validierung, z.B.

- Qualitativer Vergleich der Scores und dem Inhalt der Nachricht

- Überprüfung besonders “positiver” oder “negativer” Nachrichten

- ggf. Vergleich verschiedener Sentiment Scores

- Weiterführende Analysen, z.B.

- Verteilung der Sentiment Scores nach Streamer oder Länge der Nachrichten

- Wichtig: Bezug zur Forschungsfrage!

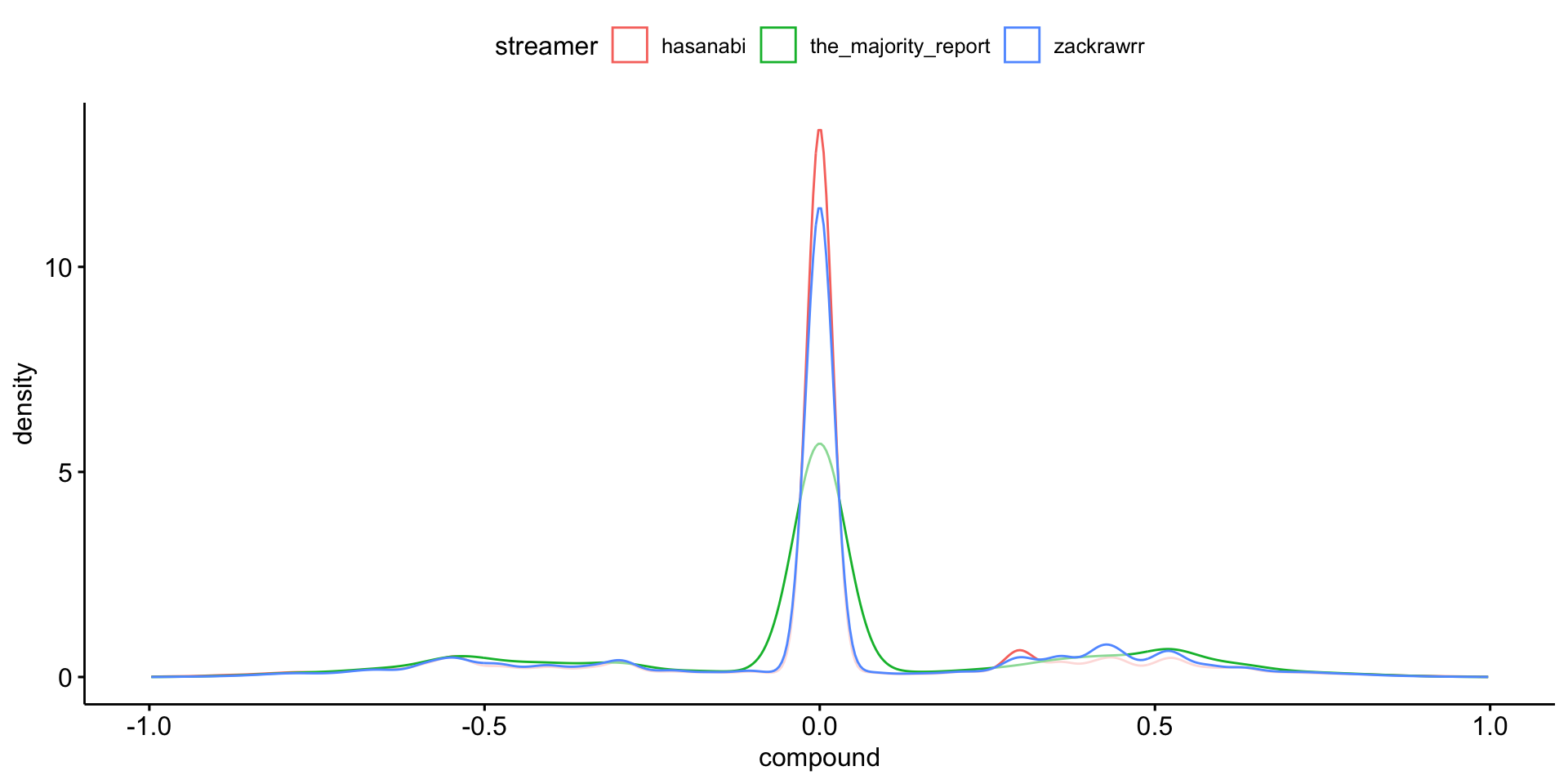

Unterschiedliche Emotionalität des Chats?

Beispiel für weiterführende Analyse: Sentiment Scores nach Streamer

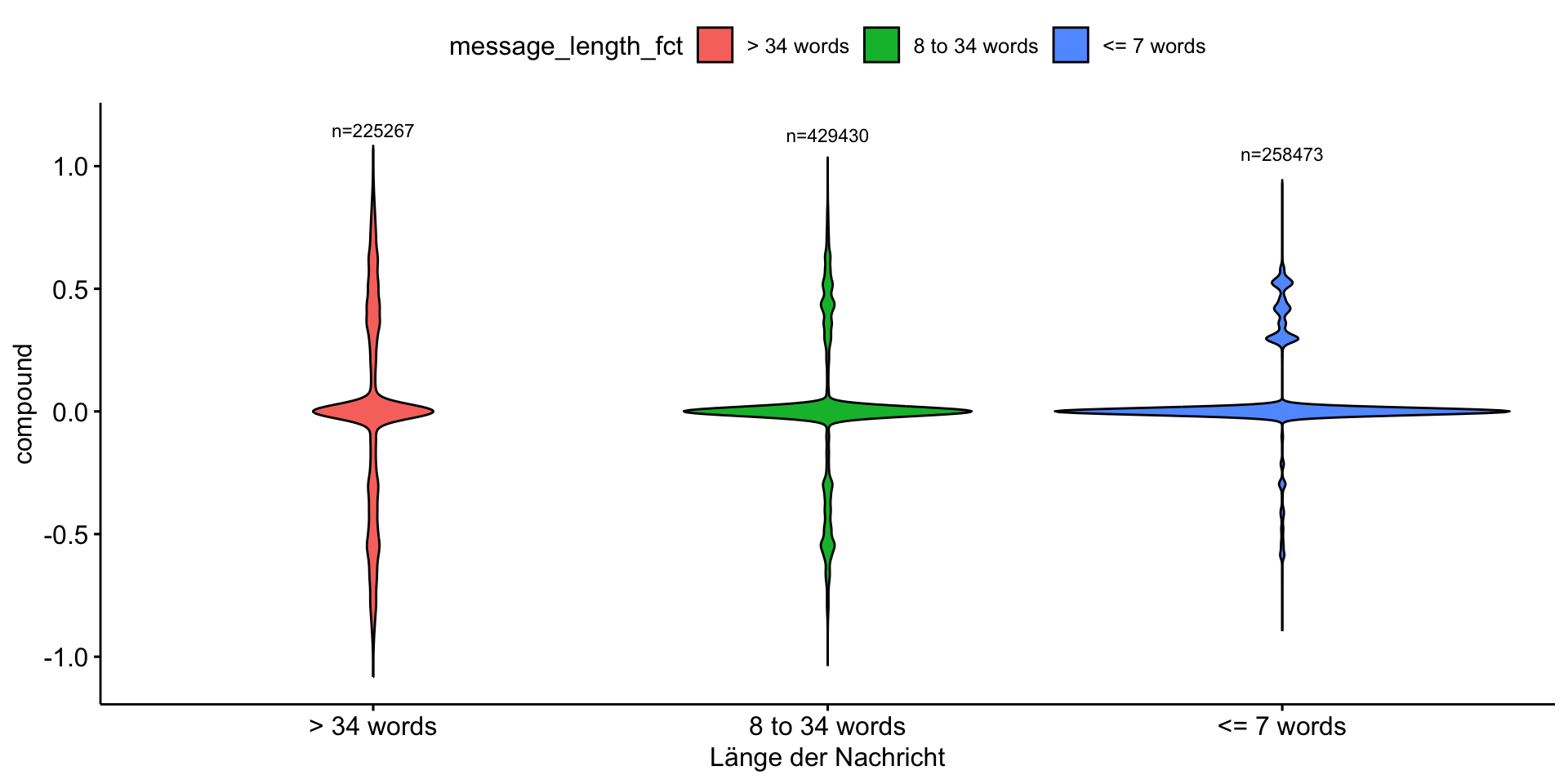

Und was machen wir jetzt damit?

Beispiel für weiterführende Analyse: Sentiment Scores nach Länge der Nachrichten

Expand for full code

chats_sentiment %>%

mutate(message_length_fct = case_when(

message_length <= 7 ~ "<= 7 words",

message_length > 7 & message_length <= 34 ~ "8 to 34 words",

message_length >= 34 ~ "> 34 words")

) %>%

group_by(message_length_fct) %>%

mutate(n = n()) %>%

ggviolin(

x = "message_length_fct",

y = "compound",

fill = "message_length_fct"

) +

stat_summary(

fun.data = function(x) data.frame(y = max(x) + 0.15, label = paste0("n=", length(x))),

geom = "text",

size = 3,

color = "black"

) +

labs(

x = "Länge der Nachricht"

)

Validierung, Validierung, Validierung

Überprüfung besonders “positiver” Nachrichten

chats_sentiment %>%

filter(compound >= 0.95) %>%

arrange(desc(compound)) %>%

select(message_content, compound) %>%

head(n = 3) %>%

gt() %>% gtExtras::gt_theme_538()| message_content | compound |

|---|---|

| mizkif is so handsome and smart <3 mizkif is so handsome and smart <3 mizkif is so handsome and smart <3 mizkif is so handsome and smart <3 mizkif is so handsome and smart <3 mizkif is so handsome and smart <3 mizkif is so handsome and smart <3 mizkif is so handsome and smart <3 | 0.997 |

| hasPray PLEASE GIVE ME THE STRENGTH TO NOT GET BANNED TODAY hasPray PLEASE GIVE ME THE STRENGTH TO NOT GET BANNED TODAY hasPray PLEASE GIVE ME THE STRENGTH TO NOT GET BANNED TODAY hasPray PLEASE GIVE ME THE STRENGTH TO NOT GET BANNED TODAY hasPray PLEASE GIVE ME THE STRENGTH TO NOT GET BANNED TODAY hasPray PLEASE GIVE ME THE STRENGTH TO NOT GET BANNED TODAY | 0.996 |

| hasPray PLEASE GIVE ME THE STRENGTH TO NOT GET BANNED TODAY hasPray PLEASE GIVE ME THE STRENGTH TO NOT GET BANNED TODAY hasPray PLEASE GIVE ME THE STRENGTH TO NOT GET BANNED TODAY hasPray PLEASE GIVE ME THE STRENGTH TO NOT GET BANNED TODAY hasPray PLEASE GIVE ME THE STRENGTH TO NOT GET BANNED TODAY hasPray PLEASE GIVE ME THE STRENGTH TO NOT GET BANNED TODAY | 0.996 |

Validierung, Validierung, Validierung

Überprüfung besonders “negativer” Nachrichten

chats_sentiment %>%

filter(compound <= -0.95) %>%

arrange(compound) %>%

select(message_content, compound) %>%

head(n = 3) %>%

gt() %>% gtExtras::gt_theme_538()| message_content | compound |

|---|---|

| pepeMeltdown OH SHIT MY OIL FUCK FUCK FUCK pepeMeltdown OH SHIT MY OIL FUCK FUCK FUCK pepeMeltdown OH SHIT MY OIL FUCK FUCK FUCK pepeMeltdown OH SHIT MY OIL FUCK FUCK FUCK | -0.997 |

| but why kill more birdsbut why kill more birdsbut why kill more birdsbut why kill more birdsbut why kill more birdsbut why kill more birdsbut why kill more birds | -0.996 |

| cry bully ass losers KEKL cry bully ass losers KEKL cry bully ass losers KEKL cry bully ass losers KEKL cry bully ass losers KEKL | -0.996 |

Validierung, Validierung, Validierung

Wersendert besonders negative Nachrichten?

chats_sentiment %>%

filter(compound >= 0.95) %>%

sjmisc::frq(

user_name,

min.frq = 5,

sort.frq = "desc")user_name <character>

# total N=289 valid N=289 mean=85.70 sd=50.72

Value | N | Raw % | Valid % | Cum. %

-----------------------------------------------------

notilandefinitelynot | 17 | 5.88 | 5.88 | 5.88

dirty_barn_owl | 16 | 5.54 | 5.54 | 11.42

aliisontw1tch | 7 | 2.42 | 2.42 | 13.84

omnivalor | 7 | 2.42 | 2.42 | 16.26

x7yz42 | 6 | 2.08 | 2.08 | 18.34

chakek1993414 | 5 | 1.73 | 1.73 | 20.07

doortoratworld | 5 | 1.73 | 1.73 | 21.80

muon_2ms | 5 | 1.73 | 1.73 | 23.53

n < 5 | 221 | 76.47 | 76.47 | 100.00

<NA> | 0 | 0.00 | <NA> | <NA>Was nehmen wir mit?

Kurze Zusammenfassung der Inhalte zur Sentimentanalyse

- Verschiedene Möglichkeiten (Modelle, Dictionaries, etc), Sentimentanalyse in R durchzuführen

- Die verschiedene Möglichkeiten haben unterschiedliche Vor- und Nachteile

- Allgemein gilt:

- Die Wahl des Modells hängt von der spezifischen Forschungsfrage und den verfügbaren Daten ab

- Validieren, Validieren, Validieren (& Optimieren!)

Aber: Wie sinnvoll und aussagekräftig sind (unsupervised) Sentimentanalysen in der Praxis?

Time for questions

Design your own research (design)

👥 Entwicklung Forschungsfrage & methodisches Vorgehen

Goodbye theory, hello practice!

Ein Blick auf die kommenden Sitzungen

- Abschluss der inhaltlichen Sitzungen ➜ “Projektphase”

- Ziel: Durchführung einer “Mini-Studie”

Entwicklung einer Forschungsfrage (auf Basis der Inhalte der Vorträge) und

Anwendung mindestens einer der behandelten Methoden

auf bereitgestellte Datensätze

Fokus auf Gruppenarbeit

Zum Ablauf der nächsten zwei Sitzungen

- Fokus der nächsten Sitzungen liegt auf eigenständige Gruppenarbeit

- Grobe Struktur: Kurze Input-Session am Anfang (Fragerunde, Orgaupdates), danach Fokus auf Arbeit in den Gruppen

- Nutzt die Möglichkeit für den Austausch oder Nachfragen

- Tauscht euch untereinander aus, sprecht mit den Expert:innen der jeweiligen Sitzung!

- Ich stehe währendessen als Ansprechpartner zur Verfügung

- Denkt an die anstehenden Assignments (Präsentationsentwurf & Peer Review)!

🧪 And now … you!

Für den Rest der Sitzung: Grupppenarbeit am Projektpräsentationsentwurf

Wichtige Hinweise

- Nächste Woche (15.01.) ist die Deadline für den Entwurf der “Projektpräsentation” ( = Grundlage für das Peer Review)

- Ablauf wird nächste Woche noch detailliert besprochen!

Arbeitsauftrag

In euren Gruppen …

- beginnt die Arbeit an der Projektpräsentation (siehe QR-Code nächste Folie)

- setzt den Schwerpunkt zunächst auf die Forschungsfrage, und überlegt danach, wie ihr diese mit Hilfe der vorgestellten Methoden beantworten könnt